www.nuitdorient.com

accueil -- nous écrire -- liens -- s'inscrire -- site

Comment

les Dirigeants Arabes ont Sapé un État Palestinien

Par Roie Yellinek et Assaf Malach- Roie Yellinek est chercheur associé au BESA Center et chercheur non résident au Middle East Institute. Assaf Malach est fondateur et directeur du Jewish Statesmanship Center, maître de conférences au Shalem College et chercheur à l'Institut Shalom Hartman.

3/5/22

Source : Middle East Quarterly - Spring 2022 • volume 29 -number 2

Texte en anglais ci-dessous

Les États arabes n'ont manifesté aucun intérêt réel pour la

création d'un État palestinien, si ce n'est pour la forme.

Les

dirigeants arabes du Liban, de la Jordanie, de la Syrie, de l'Irak et de la

Ligue arabe se réunissent pour discuter de la stratégie pendant la guerre

israélo-arabe de 1948, Daraa, Syrie. Après la guerre, les États arabes ont

exploité les Palestiniens à leurs propres fins.

Si la "question palestinienne" a longtemps dominé la politique interarabe, les États arabes ont non seulement été mus par leurs propres arrière-pensées, mais ils se sont également peu préoccupés du bien-être des Palestiniens, sans parler de leur demande d'un État qui leur soit propre. Ce schéma remonte aux années du mandat (1920-48), lorsque les champions autoproclamés du mouvement panarabe naissant - le roi Fayçal d'Irak, l'émir Abdallah de Transjordanie et le roi Faruq d'Égypte - considéraient la Palestine comme faisant partie de leurs futurs empires. Cette situation a atteint son paroxysme lors de la guerre de 1948, lorsque l'assaut arabe contre Israël a été lancé dans la poursuite des objectifs impérialistes des États envahisseurs, et non pour soutenir l'autodétermination des Palestiniens.

Selon les termes du secrétaire général de la Ligue arabe, Abdel Rahman Azzam : "Abdallah devait engloutir les régions centrales montagneuses de la Palestine, avec un accès à la Méditerranée à Gaza. Les Égyptiens obtiendraient le Néguev. [La Galilée irait à la Syrie, sauf que la partie côtière jusqu'à Acre serait ajoutée au Liban "[1].

Dans les décennies qui ont suivi la guerre israélo-arabe de 1948, les États arabes ont continué à utiliser les Palestiniens à leurs propres fins, exploitant le "problème des réfugiés" nouvellement créé pour ternir la réputation internationale d'Israël et canaliser la colère de leurs sujets opprimés vers l'extérieur. Ils n'ont pratiquement rien fait pour soulager ce problème, et encore moins pour faciliter la cristallisation du nationalisme palestinien et l'obtention du statut d'État.

Ce manque constant de reconnaissance d'une nationalité palestinienne distincte par les États arabes a été le fait des principales parties au conflit israélo-arabe : la Jordanie, l'Égypte et la Syrie.

L'identité nationale jordanienne

La Jordanie a régné sur plus de Palestiniens que tout autre

État arabe, en particulier pendant son occupation de la Cisjordanie entre 1948

et 1967. Au cours de ces années, le royaume est devenu le foyer de quelque 368 000

Palestiniens qui avaient fui la guerre israélo-arabe de 1948[2], et le

gouvernement a systématiquement effacé toute trace d'une identité palestinienne

distincte dans le but de créer une

identité nationale jordanienne plus large.

Même pendant la guerre de 1948, le roi Abdallah a fait une brève visite à Jérusalem le 15 novembre où il s'est proclamé souverain de la Palestine, ainsi que de la Jordanie, et en avril 1950, la Jordanie a officiellement annexé la zone qu'elle avait occupée pendant la guerre et l'a désignée comme la "Cisjordanie du Royaume hachémite de Jordanie"[3]. "Une décennie plus tard, le petit-fils et successeur d'Abdullah, le roi Hussein, a déclaré sa ferme opposition à l'idée d'une "entité palestinienne" séparée, convoquant une conférence en janvier 1960 des loyalistes hachémites pour dénoncer "l'innovation méprisable" de l'établissement d'une entité palestinienne [4].

Les résidents palestiniens des Cisjordanie et de l'Est ont été incorporés dans le tissu social, économique et politique de la Jordanie dans une mesure bien plus importante que leurs frères dans n'importe quel autre État arabe, principalement en raison du besoin impérieux du royaume d'accroître sa faible population et en raison de la proportion élevée de réfugiés palestiniens par rapport à la population bédouine d'origine. Cela explique pourquoi la Jordanie a été le seul pays arabe à intégrer pleinement les réfugiés palestiniens de 1948. Après la prise de la Cisjordanie par les Israéliens pendant la guerre des Six Jours en juin 1967, environ 240 000 Palestiniens ont été déplacés pour la première fois et quelque 190 000 étaient des réfugiés qui avaient été déplacés en 1948, ce qui a porté la population palestinienne de la Jordanie à plus de la moitié du nombre total d'habitants du royaume[5].

La tension entre le régime hachémite et ses sujets palestiniens n'a cessé de croître au lendemain de la guerre de 1967, les organisations terroristes palestiniennes ayant créé un État dans l'État dans le royaume, transformant son territoire en tremplin pour des attaques contre Israël. L'affaire a éclaté en septembre 1970 avec une tentative d'assassinat du roi Hussein, dans le cadre d'un vaste projet de l'Organisation de libération de la Palestine (OLP) visant à renverser la monarchie hachémite et à prendre le contrôle de l'État. Cette tentative a débouché sur une confrontation totale, connue sous le nom de "septembre noir". Au milieu de violents combats, avec le massacre de milliers de civils innocents (dont beaucoup d'origine palestinienne) et une invasion syrienne limitée en soutien à l'OLP, le groupe a été expulsé de Jordanie, un processus achevé en juillet 1971. Et si cette déroute militaire n'a pas porté un coup fatal à l'OLP, qui a rapidement remplacé la Jordanie par le Liban, Hussein a poursuivi ses efforts inlassables pour affaiblir et marginaliser l'organisation et, par extension, le nationalisme palestinien. Cela a été illustré de manière éclatante par son projet de mars 1972 d'un royaume arabe uni sous sa direction comprenant la Jordanie, la Cisjordanie et la bande de Gaza, dans lequel les Palestiniens devaient jouir d'une autonomie [6]. À la grande frustration du roi, ce projet, conçu avec la bénédiction d'Israël, a suscité l'indignation générale des Arabes, en particulier en Égypte, où le gouvernement a réagi en rompant les relations diplomatiques avec la Jordanie.

Le

président égyptien Gamal Abdel Nasser (au centre) négocie un cessez-le-feu

pendant le Septembre noir entre Yasser Arafat (à gauche) et le roi Hussein de

Jordanie (à droite), Le Caire, 27 septembre 1970. Suite à une tentative de

l'OLP de subvertir la monarchie hachémite, la Jordanie expulse l'OLP de son

territoire.

La guerre du Kippour de 1973 a renforcé la position interarabe de l'OLP, la plupart des États arabes cherchant à donner du pouvoir à l'organisation pour faire avancer leurs propres positions vis-à-vis d'Israël. La Ligue arabe aurait reconnu l'OLP comme le "seul représentant du peuple palestinien" lors de son sommet d'Alger de novembre 1973 si la Jordanie n'avait pas fait dérailler cette initiative au dernier moment. Mais ce n'était qu'une victoire à la Pyrrhus, car la reconnaissance panarabe du nationalisme palestinien (et de l'OLP comme son unique champion) a été adoptée un an plus tard, lors du sommet de la Ligue arabe d'octobre 1974 dans la capitale marocaine de Rabat.

Cela a déclenché un processus de désengagement jordano-palestinien qui a culminé avec la renonciation de Hussein, en juillet 1988, aux revendications de la Jordanie sur la Cisjordanie, en faveur de l'OLP, après l'échec de trois initiatives visant à institutionnaliser les relations entre Jordaniens, Palestiniens et Israéliens. Mais le soulèvement palestinien en Cisjordanie et à Gaza (décembre 1987-septembre 1993), ou l'Intifada, a enfoncé le dernier clou dans les espoirs du roi de récupérer la Cisjordanie. La population palestinienne ne soutenait pas cette option, tandis que ses sujets bédouins craignaient que le soulèvement ne déborde sur la Cisjordanie et ne subvertisse le royaume hachémite[7]. Le soulèvement semblait avoir fermé la porte à l'idée d'un royaume unifié réincorporant les Palestiniens de Cisjordanie en tant que sujets jordaniens, tout comme le lancement en septembre 1993 du "processus de paix" d'Oslo entre Israël et l'OLP et la conclusion d'un accord de paix israélo-jordanien un an plus tard.

Mais les appels à la résurrection de l'"option jordanienne" ont refait surface au cours des décennies suivantes, reflétant une désillusion croissante à l'égard du processus d'Oslo. Du côté israélien, on s'est rendu compte que les dirigeants de l'OLP (sans parler de ceux du Hamas et du Jihad islamique) considéraient Oslo non pas comme le moyen de parvenir à une solution à deux États - Israël et un État palestinien en Cisjordanie et à Gaza - mais comme le moyen de substituer un État palestinien à Israël. Cette compréhension des motifs de l'OLP a ravivé les souvenirs de la collaboration de longue date du mouvement sioniste avec la dynastie hachémite, qui remonte au début des années 1920.

Des sentiments similaires ont été suscités du côté palestinien par la désillusion généralisée à l'égard de la nature corrompue et oppressive de l'Autorité palestinienne dominée par l'OLP, 51 % des personnes interrogées lors d'un sondage en 2013 soutenant l'"option jordanienne " - soit 10 % de plus que lors d'un sondage similaire cinq ans plus tôt [8]. Cet état d'esprit s'est reflété dans la suggestion faite en juin 2016 par le président de l'Université al-Quds, Sari Neusseibeh - qui s'était auparavant donné beaucoup de mal pour se désengager de l'héritage de son défunt père, ministre de la Défense jordanien des années 1950 - de reconsidérer une fédération jordano-palestinienne. Plus important encore, l'ancien Premier ministre jordanien Abdel Salam Majali a exprimé son soutien à l'idée, déclarant : "La Jordanie ne peut exister sans la Palestine, et la Palestine ne peut exister sans la Jordanie"[9]. Et si les idées de Nusseibeh et de Majali ne sont guère représentatives, elles indiquent que des personnalités éminentes et une grande partie de l'opinion publique soutiennent encore l'effacement de la spécificité palestinienne et la création d'une identité collective des deux côtés du Jourdain [10].

L'Égypte en tant qu'intermédiaire

Si le gouvernement égyptien n'a manifesté aucun désir d'annexer la bande de Gaza après la guerre israélo-arabe de 1948, il n'était pas plus favorable que la Jordanie au développement d'une identité nationale palestinienne ou d'un État palestinien. Au contraire, il a soumis les résidents de la bande de Gaza à un régime militaire sévère et ne leur a pas offert la citoyenneté égyptienne. Comme le président égyptien Gamal Abdel Nasser l'a déclaré à un journaliste occidental : « Les Palestiniens sont utiles aux États arabes tels qu'ils sont. Nous veillerons toujours à ce qu'ils ne deviennent pas trop puissants. Pouvez-vous imaginer une autre nation sur les rives de la Méditerranée orientale! »11]

Malgré ce point de vue, Nasser a paradoxalement contribué au développement du nationalisme palestinien en étant l'instigateur de la formation de l'OLP en 1964. Il ne l'a pas fait par souci du bien-être des Palestiniens, mais comme un moyen, explique Edward Said, "d'institutionnaliser (peut-être même de contenir) les énergies palestiniennes" et de les utiliser pour promouvoir son objectif ultime de leadership panarabe.[12] À cette fin, il a choisi Ahmad Shukeiri pour diriger l'OLP. Shukeiri était un politicien né au Liban et fidèle au président égyptien qui, à son tour, a contribué à l'installer comme secrétaire général adjoint de la Ligue arabe. Cela a assuré la soumission de l'OLP à la volonté de Nasser et l'a empêchée de poursuivre des orientations indésirables, notamment celles fondées sur le nationalisme palestinien [13].

Dans un autre paradoxe encore, c'est la guerre des Six Jours qui a donné une impulsion majeure à l'identité nationale palestinienne en desserrant l'étau égyptien. Lorsque les populations de la bande de Gaza (et de la Cisjordanie) sont passées sous la coupe d'Israël, le contrôle direct des États arabes sur ces Palestiniens s'est affaibli, permettant à l'OLP de se libérer de la domination égyptienne. Cela a été illustré par l'élection d'un président de l'OLP, Yahya Hamuda, qui n'était pas personnellement redevable à Nasser. Plus important encore, ce relâchement de la domination des États arabes a permis la prise de contrôle progressive des organes de décision de l'OLP par le groupe terroriste Fatah, qui avait auparavant rivalisé avec l'OLP pour le leadership palestinien. En 1969, avec Yasser Arafat à sa tête, le Fatah et ses factions satellites ont obtenu 45 des 105 sièges du Conseil national palestinien ; en revanche, l'Armée de libération de la Palestine, vétéran pro-égyptien, a fortement diminué, passant de 20 à 5 sièges. Avec le soutien des 28 représentants indépendants, le Fatah est parvenu à obtenir la majorité au conseil et, le 3 février 1969, Arafat est devenu président de l'OLP, poste qu'il a occupé jusqu'à sa mort en novembre 2004 et qu'il utilisera pour libérer l'organisation de la domination des États arabes [14].

Il n'est pas étonnant que les relations d'Arafat avec le successeur de Nasser, Anwar Sadat, n'aient pas été plus chaleureuses. Le rejet catégorique par Sadate de la fédération du roi Hussein, qui a conduit à une brève rupture des relations diplomatiques égypto-jordaniennes, coïncidait pleinement avec les ambitions de l'OLP. Mais la position de Sadate ne reflétait aucune sympathie pour l'organisation ou le nationalisme palestinien ; elle traduisait plutôt une réticence à voir le prestige interarabe de la Jordanie s'accroître à la suite d'une telle décision, ainsi que la crainte d'une perte correspondante du contrôle égyptien sur la question palestinienne, qui avait commencé à jouer un rôle croissant sur l'agenda international.

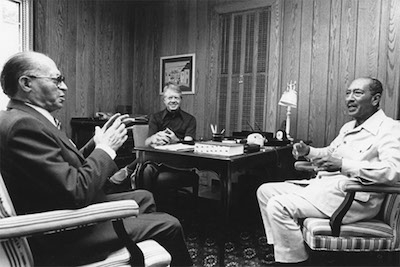

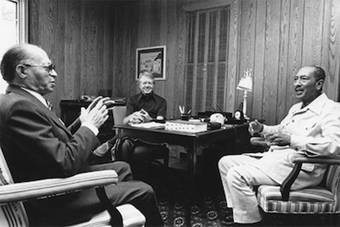

(De

gauche à droite) Le premier ministre israélien Menachem Begin, le président

Jimmy Carter, le président égyptien Anwar Sadat, Camp David, 5 septembre 1978.

Pour apaiser les partisans palestiniens, Sadate a insisté pour que le traité

égypto-israélien reconnaisse le droit des Palestiniens à l'autonomie pendant

cinq ans, leur statut final étant négocié avec Israël.

C'est pourquoi Sadate a insisté pour que le traité de paix égypto-israélien cristallisant, négocié lors du sommet de Camp David en septembre 1978, comprenne la reconnaissance du droit à l'autonomie des Palestiniens pour une période intérimaire de cinq ans, après quoi le statut final de la Cisjordanie et de la bande de Gaza serait négocié avec Israël. Mais il n'était pas prêt à aller plus loin pour apaiser les partisans de la plus célèbre cause panarabe. Lorsque le plan d'autonomie a été rejeté avec mépris par Arafat, qui a également décliné l'appel personnel du président américain Jimmy Carter à rejoindre le processus de paix,[15] Sadate n'a eu aucun scrupule à briser le tabou arabe et a signé un accord de paix séparé avec Israël.

Les relations palestino-égyptiennes se sont nettement améliorées après l'assassinat de Sadate, en grande partie grâce à l'expulsion de l'OLP du Liban en 1982 et à la détérioration de ses relations avec la Syrie, mais ni les présidents égyptiens Hosni Moubarak (1981-2011) ni Abdel Fattah Sisi (2013 à ce jour) n'ont annulé le traité de paix avec Israël ou fait un réel effort pour promouvoir un État palestinien. Au lieu de cela, ils ont utilisé leur relation avec Israël comme un levier pour renforcer leur position régionale et internationale, notamment vis-à-vis des administrations américaines successives, en jouant un rôle d'intermédiaire entre les Israéliens et les Palestiniens sans chercher à résoudre le problème.

Revendications syriennes

L'élite politique syrienne n'était pas plus favorable à l'autodétermination nationale palestinienne que ses homologues jordaniens ou égyptiens. Au cours de la décennie et demie qui a suivi son indépendance en 1946, la ligne politique sans ambiguïté prônait l'unification de la Grande Syrie, comprenant le territoire de la Syrie, de la Jordanie, du Liban et d'Israël actuels, sous le règne de Damas (le roi Abdallah de Transjordanie a également œuvré à la création de cette entité sous sa direction)[16]. Même le parti Baath panarabe, qui a pris le pouvoir lors d'un coup d'État militaire en 1963 et qui a épousé la vision d'une "nation arabe" unifiée allant "du golfe Persique à l'océan Atlantique", a continué à considérer la Palestine comme faisant partie intégrante du "sud de la Syrie". Ce point de vue était particulièrement fort pendant le règne de 30 ans (1970-2000) de Hafez Assad, qui affirmait qu'"un État du nom de Palestine n'a jamais existé"[17].

Deux ans après que la Ligue arabe ait officiellement reconnu l'OLP comme le "seul représentant du peuple palestinien", Assad a rencontré Arafat et le leader druze libanais Kamal Jumblatt. Lors de cette rencontre d'avril 1976, Assad n'a eu aucun scrupule à dire au dirigeant palestinien : « Vous ne représentez pas la Palestine comme nous le faisons. N'oubliez jamais ce point : il n'existe pas de peuple palestinien, ni d'entité palestinienne, il n'y a que la Syrie ! Vous faites partie intégrante du peuple syrien. La Palestine fait partie intégrante de la Syrie » [18].

Il n'est donc pas surprenant que le président syrien ait tenté d'utiliser l'expulsion de l'OLP du Liban par Israël en 1982 pour imposer l'hégémonie de la Syrie sur l'organisation, empêchant le retour de l'OLP dans le pays et provoquant une guerre fratricide entre les factions palestiniennes au Liban qui a fait rage pendant des années et coûté des milliers de vies. Il s'est opposé avec tout autant de véhémence à toute tentative de l'OLP d'affirmer une voie indépendante, notamment en s'engageant dans le processus d'Oslo, allant jusqu'à menacer Arafat de mort[19].

Ce point de vue a prévalu sous le règne de Bachar Assad, qui a succédé à son père à la mort de ce dernier en juin 2000. La tiédeur de la position syrienne s'est manifestée lors des conférences interarabes des années 2000 qui ont adopté des résolutions soutenant les Palestiniens sur une série de questions clés au centre de leur relation avec Israël (par ex, Non moins important, en mars 2002, la Syrie s'est opposée à la résolution 1397 du Conseil de sécurité - la première résolution contraignante sur la nécessité d'un État palestinien indépendant dans le cadre "d'une région où deux États, Israël et la Palestine, vivent côte à côte, à l'intérieur de frontières sûres et reconnues"[21]. "Et si Damas a justifié sa position par l'incapacité de la résolution à "prendre en compte les préoccupations arabes" et à "traiter la question fondamentale au cœur de ce problème - l'occupation israélienne"[22], il n'en demeure pas moins qu'elle a refusé de soutenir publiquement une résolution internationale sur l'établissement d'un État palestinien indépendant [23].

Conclusion

La guerre des Six Jours de 1967 a placé la "question palestinienne" au premier plan de l'attention internationale, l'OLP acquérant une notoriété mondiale en tant que "seul représentant du peuple palestinien", tout en maintenant ses méthodes terroristes. Cependant, les États arabes n'ont montré aucun intérêt réel pour la création d'un État palestinien, au-delà de l'habituelle annonce du bout des lèvres.

Bien que la Jordanie ait renoncé en 1988 à revendiquer la

Cisjordanie, la monarchie hachémite n'a manifesté aucun désir d'établir un État

palestinien, qu'elle craint de voir renverser son autorité, et n'a pas hésité à

faire la paix et à collaborer étroitement avec Israël, le retour éventuel du

royaume en Cisjordanie étant parfois évoqué par les deux parties. De même,

alors qu'Anouar el-Sadate s'est donné beaucoup de mal pour associer la question

palestinienne aux négociations de paix égypto-israéliennes, la formulation

convenue parlait d'une autonomie transitoire sans préciser que le statut

d'État était le résultat final, et encore moins insister sur sa réalisation.

Sadate n'a pas non plus été dissuadé d'opter pour une paix égypto-israélienne

distincte, après qu'Arafat eut rejeté son ouverture. Ajoutez à cela l'adhésion

inflexible du régime Assad à sa perception de la Palestine comme province

méridionale de la Syrie et son rejet

catégorique de toute "paix" n'impliquant pas la destruction d'Israël.

En dépit de cette approche tiède du nationalisme palestinien, des décennies de propagande antisioniste acharnée n'ont pas empêché les Palestiniens d’ancrer la "question palestinienne" dans la psyché collective régionale, au point de rendre extrêmement difficile pour les États arabes de conclure des traités de paix fonctionnels avec Israël, sans un accord palestino-israélien pro forma. Pourtant, si cet état de fait confère aux Palestiniens un certain droit de veto sur la politique interarabe, il est peu probable qu'il fasse dérailler la collaboration israélo-arabe qui s'intensifie, prend de multiples formes et devient de plus en plus manifeste, même en cas de grave détérioration des relations israélo-palestiniennes, comme le montrent les accords de normalisation de 2020 entre Israël et les EAU, Bahreïn, le Soudan et le Maroc.

Notes

[1] Efraim Karsh, Palestine Betrayed (New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 233.

[2] Efraim Karsh, "The Privileged Palestinian 'Refugees,'" Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2018.

[3] Joseph Nevo, Abdullah ve-Arviyei Eretz Israel (Tel Aviv: Shiloah Institute for Middle Eastern and African Studies, 1975), p. 111.

[4] Emile Touma, Ha-Tnua ha-Leumit ha-Falestinit veha-Olam ha-Arvi (Tel Aviv: Mifras, 1990), p. 85.

[5] Jalal Al Husseini, "Jordan and the Palestinians," in Myriam Ababsa, ed., Atlas of Jordan (Beyrouth: Presses de l'Ifpo, Institut français du Proche-Orient, 2013), p. 230.

[6] Said Aburish, Arafat: From Defender to Dictator (London: Bloomsbury, 1999), p. 127.

[7] Hassan A. Barari, "Four Decades after Black September: A Jordanian Perspective," Civil Wars, Sept. 2008, pp. 231-43.

[8] "Palestinian Public Opinion Poll No. 48," Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, Ramallah, June 2013, p. 1.

[9] Walla News (Tel Aviv), June 3, 2016.

[10] Michael Sharnoff, "Does Jordan Want the West Bank?" Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2020.

[11] Efraim Karsh, "The Palestinians' Real Enemies," Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2014.

[12] Edward Said, The Question of Palestine (New York: Vintage Books, 1980), p. 134.

[13] Said Aburish, Nasser: The Last Arab (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2004), pp. 222-3.

[14] Ibid., pp. 89-96.

[15] Efraim Karsh, Arafat's War (New York: Grove Press, 2003), pp. 49-50.

[16] Daniel Pipes, Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992); Philip S. Khoury, "Factionalism among Syrian Nationalists during the French Mandate," International Journal of Middle East Studies, Nov. 1981, pp. 441-66; Patrick Seale, The Struggle for Syria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965), pp. 13-4, 54.

[17] Yehoshafat Harkabi, Fatah ba-Estrategia ha-Arvit (Tel-Aviv: Maarachot, 1969), p. 30.

[18] Kamal Jumblatt, I Speak for Lebanon (London: Zed Press, 1982), p. 78.

[19] Karsh, "The Palestinians' Real Enemies."

[20] Eyal Zisser, Be-Shem ha-Av. Bashar Assad: Shanim Rishonot ba-Shilton (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press, 2004), p. 177.

[21] Res. 1397, U.N. Security Council, New York, Mar. 12, 2002.

[22] News release, Department of Public Information, Security Council, New York, Dec. 3, 2002.

[23] Zisser, Be-Shem ha-Av, p. 178.

..

How Arab Rulers Undermined a Palestinian State

by Roie Yellinek and Assaf Malach- Roie Yellinek is a research associate at the BESA Center and a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute. Assaf Malach is the founder and head of the Jewish Statesmanship Center, a lecturer at Shalem College, and a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute.

Middle East Quarterly - Spring 2022 • volume 29 -number 2

The Arab states have shown no real interest in Palestinian statehood

beyond the customary lip service.

|

Arab leaders of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and the Arab League meet to discuss strategy during the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, Daraa, Syria. Following the war, the Arab states exploited the Palestinians for their own ends. |

While the "Palestine question" has long dominated inter-Arab politics, not only have the Arab states been driven by their own ulterior motives, but they also have shown little concern for the well-being of the Palestinians, let alone their demand for a state of their own. This pattern dates back to the mandate years (1920-48) when the self-styled champions of the nascent pan-Arab movement—King Faisal of Iraq, Transjordan's Emir Abdullah, and Egyptian King Faruq—viewed Palestine as part of their would-be empires. This situation culminated in the 1948 war when the all-Arab assault on Israel was launched in pursuit of the invading states' imperialist goals—not in support of Palestinian self-determination.

In the words of the Arab League's secretary-general Abdel Rahman Azzam: « Abdullah was to swallow up the central hill regions of Palestine, with access to the Mediterranean at Gaza. The Egyptians would get the Negev. [The] Galilee would go to Syria, except that the coastal part as far as Acre would be added to Lebanon ».[1]

In the decades following the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the Arab states continued to use the Palestinians to their own ends, exploiting the newly created "refugee problem" to tarnish Israel's international standing and channel their oppressed subjects' anger outwards. They did practically nothing to relieve this problem, let alone to facilitate the crystallization of Palestinian nationalism and the attainment of statehood.

This consistent lack of recognition of a separate Palestinian nationality by the Arab states was perpetrated by the main parties to the Arab-Israeli conflict: Jordan, Egypt, and Syria.

Jordanian National Identity

Jordan has ruled over more Palestinians than any other Arab state, especially during its occupation of the West Bank between 1948 and 1967. In these years, the kingdom became home to some 368,000 Palestinians who fled the 1948 Arab-Israeli war,[2] and the government systematically erased all traces of a distinct Palestinian identity in an attempt to create a wider Jordanian national identity.

Even during the 1948 war, King Abdullah made a brief visit to Jerusalem on November 15 where he proclaimed himself the ruler of Palestine as well as Jordan, and in April 1950, Jordan formally annexed the area it occupied in the war and designated it the "West Bank of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan."[3] A decade later, Abdullah's grandson and successor King Hussein declared his firm opposition to the idea of a separate "Palestinian entity," convening a conference in January 1960 of Hashemite loyalists to denounce the "despicable innovation" of the establishment of a Palestinian entity.[4]

The Palestinian residents of the east and west banks were incorporated into Jordan's social, economic, and political fabric to a far greater extent than their brothers in any other Arab state, primarily due to the kingdom's dire need to boost its scarce population and because of the high ratio of Palestinian refugees vis-à-vis the original Bedouin population. This explains why Jordan was the only Arab country to integrate fully the Palestinian refugees of 1948. Following the Israeli capture of the West Bank during the Six-Day War in June 1967, about 240,000 Palestinians were displaced for the first time and some 190,000 were refugees who had been displaced in 1948, increasing Jordan's Palestinian population to more than half of the kingdom's total inhabitants.[5]

Tension between the Hashemite regime and its Palestinian subjects grew steadily in the wake of the 1967 war as the Palestinian terror organizations established a state within a state in the kingdom, transforming its territory into a springboard for attacks on Israel. Matters erupted in September 1970 with an attempt on King Hussein's life as part of a wider Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) bid to subvert the Hashemite monarchy and take over the state. This led to an all-out confrontation that came to be widely known as Black September. Amid heavy fighting with massacres of thousands of innocent civilians (including many of Palestinian descent) and a limited Syrian invasion in support of the PLO, the group was expelled from Jordan, a process completed in July 1971. And while this military routing failed to deal a mortal blow to the PLO, which quickly substituted Lebanon for Jordan as its home, Hussein continued his tireless efforts to weaken and marginalize the organization and by extension Palestinian nationalism. This was vividly illustrated by his March 1972 plan of a united Arab kingdom under his headship comprising Jordan, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, in which the Palestinians were to enjoy autonomy.[6] To the king's frustration, the plan, conceived with Israel's blessing, met with widespread Arab outrage, particularly in Egypt, where the government responded by severing diplomatic relations with Jordan.

|

Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser (center) brokers a ceasefire during Black September between Yasser Arafat (left) and Jordan's King Hussein (right), Cairo, Sept. 27, 1970. Following a PLO attempt to subvert the Hashemite monarchy, Jordan expelled the PLO from its territory. |

The 1973 Yom Kippur War boosted the PLO's inter-Arab stance as most Arab states sought to empower the organization as a means of advancing their own positions vis-à-vis Israel. The Arab League would have recognized the PLO as the "sole representative of the Palestinian people" during its November 1973 Algiers summit had Jordan not derailed the initiative at the last moment. But this was but a Pyrrhic victory as the pan-Arab recognition of Palestinian nationalism (and the PLO as its sole champion) was passed a year later—in the October 1974 Arab League summit in the Moroccan capital of Rabat.

This set in motion a process of Jordanian-Palestinian disengagement culminating in Hussein's July 1988 renunciation of Jordan's claims to the West Bank, in favor of the PLO, following the failure of three initiatives to institutionalize relations between Jordanians, Palestinians, and Israelis. But the Palestinian uprising in the West Bank and Gaza (December 1987-September 1993), or the intifada, drove the final nail in the king's hopes to regain the West Bank: The Palestinian population did not support this option while his Bedouin subjects feared the uprising would spill over into the East Bank and subvert the Hashemite kingdom.[7] The uprising seemed to have closed the lid on the idea of a unified kingdom reincorporating the West Bank's Palestinians as Jordanian subjects as did the September 1993 launching of the Israel-PLO Oslo "peace process" and the conclusion of a Jordanian-Israeli peace agreement a year later.

But calls for the resurrection of the "Jordanian option" resurfaced over the following decades, reflecting growing disillusionment with the Oslo process. On the Israeli side, the realization grew that the PLO leadership (let alone those of Hamas and Islamic Jihad) viewed Oslo not as the means to a two-state solution—Israel and a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza—but for the substitution of a Palestinian state in place of Israel. This understanding of PLO motives kindled warm memories of the Zionist movement's long-standing collaboration with the Hashemite dynasty dating back to the early 1920s.

Similar sentiments were aroused on the Palestinian side by the widespread disillusionment with the corrupt and oppressive nature of the PLO-dominated Palestinian Authority, with 51 percent of respondents to a 2013 poll supporting the "Jordanian option"—roughly 10 percent more than in a similar poll five years earlier.[8] This mindset was reflected in the June 2016 suggestion by al-Quds University president Sari Neusseibeh—who had previously gone to great lengths to disengage himself from his late father's legacy as the 1950s Jordanian defense minister—for reconsideration of a Jordanian-Palestinian federation. More importantly, former Jordanian prime minister Abdel Salam Majali voiced support for the idea, stating, "Jordan cannot exist without Palestine, and Palestine cannot exist without Jordan."[9] And while Nusseibeh's and Majali's ideas are hardly representative, they indicate that prominent figures and substantial public opinion still support the blurring of Palestinian distinctiveness and the creation of a collective identity on both sides of the Jordan River.[10]

Egypt as Intermediary

While Egypt's government indicated no desire to annex the Gaza Strip after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, it was no more amenable than Jordan to the development of Palestinian national identity or Palestinian statehood. Instead, it subjected the residents of the Gaza Strip to a harsh military regime and did not offer them Egyptian citizenship. As Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser told a Western journalist:

The Palestinians are useful to the Arab states as they are. We will always see that they do not become too powerful. Can you imagine yet another nation on the shores of the eastern Mediterranean![11]

Despite this view, Nasser was paradoxically instrumental in the development of Palestinian nationalism by instigating the formation of the PLO in 1964. He did so not out of concern for Palestinian wellbeing but as a means, Edward Said explains, of "institutionalizing (perhaps even containing) Palestinian energies" and using them to promote his ultimate goal of pan-Arab leadership.[12] To this end, he selected Ahmad Shukeiri to head the PLO. Shukeiri was a Lebanon-born politician loyal to the Egyptian president who in turn helped install Shukeiri as deputy secretary-general of the Arab League. This ensured the PLO's subservience to Nasser's will and prevented it from pursuing undesirable directions, particularly those based on Palestinian nationalism.[13]

In yet another paradox, it was the Six-Day War that gave a major boost to Palestinian national identity by loosening the grip of the Egyptian chokehold. When the Gaza Strip (and West Bank) populations came under Israel's rule, the Arab states' direct control over these Palestinians weakened, allowing the PLO to break from Egyptian dominance. This was illustrated by the election of a PLO chairman, Yahya Hamuda, who was not personally beholden to Nasser. More importantly, this loosening of the Arab states' domination allowed for the creeping takeover of the PLO's decision-making organs by the Fatah terror group, which had previously vied with the PLO for Palestinian leadership. By 1969, with Yasser Arafat at its head, Fatah and its satellite factions had gained 45 of the Palestinian National Council's 105 seats; in contrast, the veteran pro-Egyptian Palestine Liberation Army dropped sharply from 20 to 5 seats. With the support of the 28 independent representatives, Fatah managed to win a majority on the council, and on February 3, 1969, Arafat became PLO chairman, a post he held until his death in November 2004, and which he would use to free the organization from the Arab states' domination.[14]

Small wonder that Arafat's relations with Nasser's successor Anwar Sadat were no warmer. Sadat's outright rejection of King Hussein's federation, which led to a brief severance of Egyptian-Jordanian diplomatic relations, fully coincided with the PLO's ambitions. But Sadat's stance reflected no sympathy with the organization or with Palestinian nationalism; rather, it indicated a reluctance to see a surge in Jordan's inter-Arab prestige as a result of such a move as well as fear of the corresponding loss of Egyptian control over the Palestine issue, which had started to play a growing role on the international agenda.

|

(Left to right) Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin, President Jimmy Carter, Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, Camp David, Sept. 5, 1978. To placate Palestinian supporters, Sadat insisted that the Egyptian-Israeli treaty recognize the Palestinians' right to autonomy for five years with their final status negotiated with Israel. |

For this reason, Sadat insisted that the crystallizing Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, negotiated at the September 1978 Camp David summit, must include recognition of the Palestinians' right to autonomy for an interim period of five years, after which the West Bank and Gaza Strip's final status would be negotiated with Israel. Yet this was as far as he was prepared to go in placating supporters of the most celebrated pan-Arab cause. When the autonomy plan was contemptuously dismissed by Arafat, who also declined U.S. president Jimmy Carter's personal appeal to join the peace process,[15] Sadat had no qualms about breaking the Arab taboo and signed a separate peace agreement with Israel.

Palestinian-Egyptian relations improved significantly after Sadat's assassination, largely due to the PLO's 1982 expulsion from Lebanon and its deteriorating relations with Syria, but neither Egyptian presidents Hosni Mubarak (1981-2011) nor Abdel Fattah Sisi (2013 to date) cancelled the peace treaty with Israel or made a real effort to promote Palestinian statehood. Instead, they used their relationship with Israel as a lever to enhance their regional and international position, especially vis-à-vis successive U.S. administrations, by playing an intermediary role between Israelis and Palestinians without seeking resolution.

Syrian Claims

The Syrian political elite was no more sympathetic to Palestinian national self-determination than its Jordanian or Egyptian counterparts. In the decade-and-a-half following its independence in 1946, the unambiguous political line advocated the unification of Greater Syria comprising the territory of present-day Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel, under Damascus's reign (Transjordan's King Abdullah also strove for the creation of this entity under his headship).[16] Even the pan-Arab Baath party, which seized power in a military coup in 1963 and which espoused the vision of a unified "Arab nation" from "the [Persian] Gulf to [Atlantic] Ocean," continued to view Palestine as an integral part of "southern Syria." This view was especially strong during the 30-year reign (1970-2000) of Hafez Assad, who claimed that "a state by the name of Palestine has never existed."[17]

Two years after the Arab League had formally recognized the PLO as the "sole representative of the Palestinian people," Assad met with Arafat and Lebanese Druze leader Kamal Jumblatt. In the April 1976 meeting, Assad had no qualms about telling the Palestinian leader that you do not represent Palestine as we do. Never forget this one point; there is no such thing as a Palestinian people, no such thing as a Palestinian entity, there is only Syria! You are an integral part of the Syrian people. Palestine is an integral part of Syria.[18]

It is no surprise, then, that the Syrian president attempted to use Israel's 1982 expulsion of the PLO from Lebanon to impose Syria's hegemony on the organization, preventing the PLO's return to the country and instigating an internecine war among the Palestinian factions in Lebanon that raged for years and cost thousands of lives. He was no less vehemently opposed to any attempt by the PLO to assert an independent course—notably by embarking on the Oslo process—going so far as to threaten Arafat with death.[19]

This outlook prevailed under the rule of Bashar Assad, who succeeded his father upon the elder's death in June 2000. The lukewarm Syrian position was manifested at inter-Arab conferences in the 2000s that adopted resolutions backing the Palestinians over a host of key issues at the center of their relationship with Israel (e.g., sovereignty over the Temple Mount and Jerusalem).[20] No less important, in March 2002, Syria opposed Security Council Resolution 1397—the first binding resolution on the need for an independent Palestinian state as part of "a region where two States, Israel and Palestine, live side by side within secure and recognized borders."[21] And while Damascus justified its position by the resolution's failure to "take into account any Arab concerns" and to "deal with the root question at the heart of this issue—the Israeli occupation,"[22] the fact remains that it withheld public support for an international resolution on the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.[23]

Conclusion

The 1967 Six-Day War placed the "Palestine question" at the forefront of international attention with the PLO gaining worldwide prominence as "the sole representative of the Palestinian people" while maintaining its terrorist ways. But, the Arab states have shown no real interest in Palestinian statehood beyond the customary lip service.

Despite Jordan's 1988 renunciation of claims to the West Bank, the Hashemite monarchy has neither shown any desire for the establishment of a Palestinian state, which it fears might subvert its rule, nor shied away from making peace and closely collaborating with Israel with the kingdom's possible return to the West Bank occasionally mooted by both sides. Similarly, while Anwar Sadat went to great lengths to attach the Palestinian issue to the Egyptian-Israeli peace negotiations, the agreed formulation spoke about a transient autonomy without specifying statehood as the end result, let alone insisting on its attainment. Nor was Sadat deterred from opting for a separate Egyptian-Israeli peace once Arafat rejected his overture. Add to this the Assad regime's adamant subscription to its perception of Palestine as Syria's southern province and its outright rejection of "peace" that did not entail Israel's destruction.

This half-hearted approach toward Palestinian nationalism notwithstanding, decades of staunch anti-Zionist propaganda have entrenched the "Palestine question" in the collective regional psyche to the extent of making it exceedingly difficult for the Arab states to conclude functional peace treaties with Israel without a pro forma Palestinian-Israeli agreement. Yet while this state of affairs gives the Palestinians some veto power over inter-Arab politics, it is unlikely to derail the intensifying, multifaceted, and increasingly overt Arab-Israeli collaboration even in the event of severe deterioration in Israeli-Palestinian relations, as the 2020 normalization agreements between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco show.

Notes

[1] Efraim Karsh, Palestine Betrayed (New Heaven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 233.

[2] Efraim Karsh, "The Privileged Palestinian 'Refugees,'" Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2018.

[3] Joseph Nevo, Abdullah ve-Arviyei Eretz Israel (Tel Aviv: Shiloah Institute for Middle Eastern and African Studies, 1975), p. 111.

[4] Emile Touma, Ha-Tnua ha-Leumit ha-Falestinit veha-Olam ha-Arvi (Tel Aviv: Mifras, 1990), p. 85.

[5] Jalal Al Husseini, "Jordan and the Palestinians," in Myriam Ababsa, ed., Atlas of Jordan (Beyrouth: Presses de l'Ifpo, Institut français du Proche-Orient, 2013), p. 230.

[6] Said Aburish, Arafat: From Defender to Dictator (London: Bloomsbury, 1999), p. 127.

[7] Hassan A. Barari, "Four Decades after Black September: A Jordanian Perspective," Civil Wars, Sept. 2008, pp. 231-43.

[8] "Palestinian Public Opinion Poll No. 48," Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, Ramallah, June 2013, p. 1.

[9] Walla News (Tel Aviv), June 3, 2016.

[10] Michael Sharnoff, "Does Jordan Want the West Bank?" Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2020.

[11] Efraim Karsh, "The Palestinians' Real Enemies," Middle East Quarterly, Spring 2014.

[12] Edward Said, The Question of Palestine (New York: Vintage Books, 1980), p. 134.

[13] Said Aburish, Nasser: The Last Arab (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2004), pp. 222-3.

[14] Ibid., pp. 89-96.

[15] Efraim Karsh, Arafat's War (New York: Grove Press, 2003), pp. 49-50.

[16] Daniel Pipes, Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992); Philip S. Khoury, "Factionalism among Syrian Nationalists during the French Mandate," International Journal of Middle East Studies, Nov. 1981, pp. 441-66; Patrick Seale, The Struggle for Syria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965), pp. 13-4, 54.

[17] Yehoshafat Harkabi, Fatah ba-Estrategia ha-Arvit (Tel-Aviv: Maarachot, 1969), p. 30.

[18] Kamal Jumblatt, I Speak for Lebanon (London: Zed Press, 1982), p. 78.

[19] Karsh, "The Palestinians' Real Enemies."

[20] Eyal Zisser, Be-Shem ha-Av. Bashar Assad: Shanim Rishonot ba-Shilton (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press, 2004), p. 177.

[21] Res. 1397, U.N. Security Council, New York, Mar. 12, 2002.

[22] News release, Department of Public Information, Security Council, New York, Dec. 3, 2002.

[23] Zisser, Be-Shem ha-Av, p. 178.

Source: https://www.meforum.org/63037/how-arab-rulers-undermined-a-palestinian-state?goal=0_086cfd423c-c5ef898119-33965461&mc_cid=c5ef898119&mc_eid=c8855f5353

Follow Middle East and Terrorism on Twitter